I believe in the sun even when it is not shining;

I believe in love even when feeling it not;

I believe in God even when he is silent.

— An inscription on the wall of a cellar in Cologne where a number of Jews hid themselves for the entire duration of the war.

UPDATE (4 April 2021): I have found a primary source for this quotation. Be sure to read part V of this series.

Many people have found inspiration in this quotation and the story behind it, and have passed it along, sometimes with embellishments. In the first two posts in this series, I wrote about the embellishments, and tracked down what seems to be the earliest written source for the quotation — a source that gives the words in a different order, with a different meaning. If you have thought about using this quotation yourself, I hope you are considering now how best to be true to its history; and I hope that you might also share my discomfort about how often this story about Jews in the Holocaust has been used specifically by Christians to support their own faith — and not so much by Jews, to support theirs.

So when I tell you now that the quotation, exactly as given above,1 is given on page 81 of The Tiger Beneath the Skin, a collection of stories published in 1947 by a Jewish Zionist named Zvi Kolitz,2 perhaps you will feel some relief. There’s an early source, written by a Jew, with the words in the familiar order! We can lay aside our concerns, and go ahead and use the quotation as it is given above, with no qualms!

Or we can look more closely.

Zvi Kolitz was born in the little town of Alytus, Lithuania. In the 1930s he went to Italy for school, and by 1940 he had moved to Jerusalem.3 Kolitz was part of Zabotinsky’s Zionist Revisionist movement, as well as a member of the paramilitary Irgun, which was devoted to ejecting the British from Palestine. He was imprisoned by the British a couple of times, and yet he also joined the British Army in 1942 and served as the Chief Recruiting Officer for the British Army in Jerusalem, to help build up the forces fighting against Germany.

After the war, he traveled widely, representing the Zionist Revisionists (officially) and the Irgun (secretly). As an emissary of the Zionist World Congress, he traveled to Argentina in 1946, and later to Mexico and the United States.

In 1947, Kolitz published The Tiger Beneath the Skin, the collection of short stories mentioned above. The book is a powerful document of its time, a reaction to the horrors of the Holocaust, filled with rage, and sorrow, and dreams of mystical vengeance.

In “The Curse of the Rabbi of Rytzk,”4 a blind rabbi curses the German soldier who is about to kill him as he sits at prayer in his home. “Know then that it has been decreed from Heaven that you will not fall like a soldier in battle, but as a hunted criminal after the war shall have ended in your defeat. Your death will be delayed by Heaven so that you may live to witness the vengeance of the God of Vengeance on the evildoers of the earth. […] Your comrades […] will not know that God is preserving you only in order to avenge Himself on you […]” The soldier succeeds in his future battles, but he is haunted by a vision of the blind rabbi’s eye, filled with blood. He risks his life unnecessarily while fighting, and even tries to kill himself, but he always survives, and is driven mad by the constant vision of the rabbi’s eye. He escapes from the asylum where he had been placed and flees into a deep Russian forest, where, for a long time afterwards, Russian peasants tell of seeing a man walking on all fours, screaming horribly day and night.

In “The Legend of the Dead Poppy,”5 a mother and daughter are imprisoned in Treblinka. The daughter, 14 years old, is caught trying to escape, and is thrown alive into the camp oven. The daughter’s ash and bone is crushed with the remains of others and used as fertilizer for the fields of poppies surrounding the camp, and the mother believes she will be able to find the flowers that contain the soul of her daughter. She creeps through a wide spot in the electrified fence one night and wanders the fields, until she finds two poppies on one stem that look to her like her daughter’s eyes. She lies down with the flowers until morning, when the guards find her and drag her back to the camp, still holding the double-stemmed poppy. She, and the flowers, are thrown together into the oven. A few days later, when the Nazis pick poppies from the fields to decorate the tables at a celebration of Hitler’s birthday, the water in the vases turns blood red.

There are more stories in the book, as simple and as intense as these two. They are not gentle. They are not resigned. They echo the epigraph that Kolitz chose for the book, the epigraph that gives the book its title:

… For we are tired of bearing our sadness alone

And the secrets of tigers under the skin of a lamb.

—Ury Zvi Greenberg

Most of the stories from The Tiger Beneath the Skin have been forgotten, but one of them has become a classic of Holocaust fiction and has taken on a life of its own: “Yossel Rakover’s Appeal to God.”6

“Yossel Rakover” begins with its own epigraph: the “I believe in the sun” quotation, as given at the top of this page. But in contrast to the quiet, patient, passive faith suggested by the epigraph, “Yossel Rakover” tells a story of violent struggle, armed resistance, and argumentative faith. The story uses a framing device: It begins,

In the ruins of the ghetto of Warsaw, among heaps of charred rubbish, there was found, packed tightly into a small bottle, the following testament, written during the ghetto’s last hours by a Jew name Yossel Rakover.

Yossel Rakover is leaving a note for the future, telling the story of the final hours of the ghetto before the Nazis completely destroy it, and telling of his own imagined argument with God. He begins by describing how his wife and six children have all died by violence or disease, as they fled the countryside, came to Warsaw, and struggled to survive in the ghetto. He and a band of compatriots are in one of the last houses standing, and they have been fighting the German forces for days, with guns and Molotov cocktails. The house is crumbling, most of his friends have been killed, and Yossel Rakover is preparing for his own death: He has three bottles of gasoline, two of which he will use to kill Germans, and one he will soak himself with, so that when the Germans finally attack he will die quickly. Yossel Rakover believes in God, there is no question about that — but he questions God’s silence, and he wonders at how great God’s patience must be to allow the destruction of His people without interfering. Yossel Rakover argues with God, questions Him, accuses Him, and does not excuse Him. Yossel Rakover writes,

I die peacefully, but not complacently; persecuted, but not enslaved; embittered, but not cynical; a believer, but not a supplicant; a lover of God, but not blind amen-sayer of His.

And he closes with the words of Psalm 31:5 — Into your hands, O Lord, I consign my soul — which were also, according to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus’s last words on the cross.

So yes, it is true: One can find the “I believe in the sun” quotation in Zvi Kolitz’s book. But to think that they summarize “Yossel Rakover’s Appeal to God” is to misread the story. “Yossel Rakover” undermines those words, and tells of a different kind of faith. “Yossel Rakover” is the tiger’s secret; “I believe in the sun” is the skin of the lamb.7

Before closing this installment, I should briefly say something about the amazing history8 of the story “Yossel Rakover’s Appeal to God.” Zvi Kolitz wrote the piece in Yiddish, and it first appeared (as “Yosl Rakovers vendung tsu got”) in the September 25, 1946 issue of Di Yiddishe Tsaytung, a newspaper serving the large Jewish community in Buenos Aires. Kolitz wrote the story when he was in Argentina in 1946; the editor of the newspaper invited him to contribute something to the paper to help commemorate the upcoming Yom Kippur observances.

The English version of the story that appeared in The Tiger Beneath the Skin was translated from the Yiddish original by Shmuel Katz9, who edited out some short passages whose theology he may not have agreed with. This 1947 translation apparently did not have much influence in literary society. However, in 1953 an anonymous Argentinian Jew sent a typewritten transcription of “Yosl Rakovers vendung tsu got” — without Zvi Kolitz’s name attached, and without any indication that the work was fictional — to the editor of a European Yiddish quarterly publication called Di Goldene Keyt. The story was published, but now it was taken to be fact, not fiction. It was widely spread, read over the radio in Germany, and discussed by public scholars, including Thomas Mann.

It took nearly 40 years for it to be firmly established once again that the piece was not an accounting of actual events, and was in fact written by Zvi Kolitz.

At present there are at least two English translations of the complete original text from Di Yiddishe Tsaytung. One, by Jeffry V. Mallow and Frans Jozef van Beeck, appears in the CrossCurrents paper listed in the bibliography below. The other, by Carol Brown Janeway, appears in the short book Yosl Rakover Talks to God10, and can also be found online here.

I highly recommend reading one of these translations. The story is compelling, and it will change your perception of the “I believe in the sun” quotation that this series of posts is devoted to.

The posts in this series:

1. Look away

2. The Friend

3. The secrets of tigers

4. Conclusion

Added 4 April 2021:

5. The source

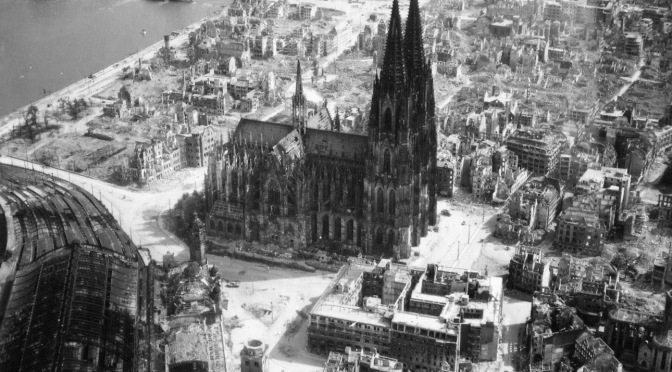

Cover image:

Public domain image from Pixabay.com, uploaded by user Marcel Langthim. Original here.

Bibliography:

Kolitz, Zvi. The Tiger Beneath the Skin: Stories and Parables of the Years of Death. New York: Creative Age Press, 1947.

Kolitz, Zvi. Yosl Rakover Talks to God. Translated by Carol Brown Janeway; from the edition established by Paul Badde; with afterwords by Emmanuel Levinas and Leon Wieseltier. New York: Pantheon Books, 1999.

Kolitz, Zvi, Jeffry V. Mallow, and Frans Jozef van Beeck. “Yossel Rakover’s Appeal to God: A Story Written Especially for Di Yiddishe Tsaytung.” CrossCurrents 44, no. 3 (1994): 362–377.

- Except that where I have put semicolons, the original had commas. ↩

- Zvi Kolitz, The Tiger Beneath the Skin: Stories and Parables of the Years of Death (New York: Creative Age Press, 1947). ↩

- My source for this bibliographic information is the essay by Paul Badde in the 1999 edition of Yosl Rakover Talks to God, listed in the bibliography. I am not sure how accurate Paul Badde is. He gives Kolitz’s birth year as 1919, while the Library of Congress information at the front of the book gives Kolitz’s birth year as 1913, and Kolitz’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times says that he was 89 years old when he died in 2002. This all seems in line with the confusion that surrounds the history of “Yosl Rakover.” ↩

- Kolitz, The Tiger Beneath the Skin, 1–14. ↩

- Kolitz, The Tiger Beneath the Skin, 61–68. ↩

- Kolitz, The Tiger Beneath the Skin, 81–95. ↩

- Thank you, Bella. ↩

- This history is gleaned from the 1994 CrossCurrents paper listed in the bibliography. It’s also outlined in Paul Badde’s essay, but the CrossCurrents accounting is easier to follow. ↩

- Zvi Kolitz, Jeffry V. Mallow, and Frans Jozef van Beeck, “Yossel Rakover’s Appeal to God: A Story Written Especially for Di Yiddishe Tsaytung,” CrossCurrents 44, no. 3: 374. ↩

- Zvi Kolitz, Yosl Rakover Talks to God, translated by Carol Brown Janeway (New York: Pantheon Books, 1999), 3–25. ↩